The potential impact of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) on exports to the European market.

The potential impact of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) on exports to the European market.

Introduction:

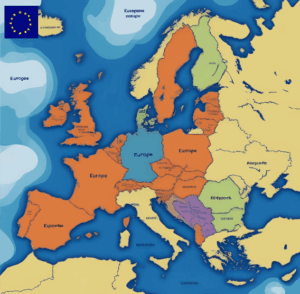

Officially legislated as part of the EU Green Deal, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) came into effect in its transitional phase in October 2023, with full implementation expected by 2026. It seeks to level the playing field for European industries subject to the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) by imposing a carbon cost on imports of high-emission goods. CBAM effectively externalizes the EU’s climate standards into the international trade order, creating both legal innovation and controversy.

The mechanism applies to imports of carbon-intensive goods such as iron, steel, cement, aluminum, fertilizers, hydrogen, and eventually electricity. Importers are required to purchase CBAM certificates corresponding to the embedded carbon emissions in these goods. Over time, these certificates will be priced similarly to allowances under the EU ETS. In its transitional phase (2023–2025), the CBAM requires importers to report emissions without financial transactions; but after 2026, full pricing will apply.

The legal controversy arises from concerns over the mechanism’s compatibility with core WTO rules. While the EU maintains that CBAM complies with Articles I (Most-Favoured Nation) and III (National Treatment) of the GATT, as well as the environmental exceptions under Article XX, critics argue it functions as a disguised protectionist measure. Countries from the Global South, including India, Brazil, South Africa, and China, have voiced strong objections, calling CBAM a form of “green protectionism”.

CBAM AND ITS IMPACT ON INDIAN TRADE:

Since 2024, India has increasingly focused its attention on the potential impact of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) on its exports to the European market. However, the implications for India go well beyond a simple decline in export volumes or economic losses. CBAM raises critical concerns regarding its alignment with the principles of equity, efficiency, and established international legal frameworks—particularly the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC) and the obligations under the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements.

- The implementation of the CBAM presents significant administrative and technical challenges for Indian producers. The reporting obligation, effective from October 2023, mandates the disclosure of the quantity of imported goods, their embedded carbon emissions, and any applicable carbon costs incurred in the exporting country. This

requirement poses significant challenge for Indian exporters, who in the absence of proper technological means must adhere to the EU standards by monitoring, calculating, reporting, and verifying emissions. India’s inadequate data infrastructure for emissions collection may necessitate default emission data usage, potentially resulting in increased costs due to mark-ups imposed by the European Council.

- The second phase of the CBAM will place a financial burden on EU importers. Starting in 2026, importers must purchase CBAM certificates for the emissions embedded in goods imported into the EU, effectively acting as a tax at the border. This could lead to higher prices for CBAM-covered goods in the European market, potentially affecting India’s exports in specific sectors and their competitiveness, depending on production emission intensity and reliance on the EU market. Indian exporters should evaluate the financial impact of the CBAM certificate requirement, especially if EU importers pass these costs onto them.

- India is expected to be significantly affected by the CBAM in its exports of aluminum and iron and steel, as the EU is a major market for these commodities. Around 27% ($2.7 billion) of India’s aluminum and 38% ($3.7 billion) of its steel exports go to the EU[10]. The impact of the CBAM’s “tax” on Indian exports will arguably be higher due to its reliance on coal-fired electricity.

INDIA’S RESPONSE TO CBAM

India has strongly opposed the CBAM at the WTO and is taking proactive measures domestically to protect its interests and promote sustainable development. These measures include aiming to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030 and introducing a Carbon Credit Trading System (“CCTS”).

Furthermore, India could pursue negotiations with the EU and the UK for the establishment of Free Trade Agreements (“FTA”). Discussions with the EU should prioritize the allocation of CBAM revenues towards supporting green transitions in developing countries.

In bilateral negotiations, India could also explore the possibility of including clauses that provide for a deferral of the CBAM and its application. As an additional strategy to protect Indian interests, India is contemplating the implementation of its own carbon tax on exports to the EU, with the proceeds potentially used to fund domestic clean energy initiatives.

References Used:

- https://www.eurofer.eu/assets/Uploads/Consistency-CBAM_ETS_WTO_legal-analysis.pdf

- https://www.azbpartners.com/bank/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-and-its-impact in-india/#_ftnref1

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_21_3661

- https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/allowances/leakage_en

- Miller, D. (2024) ‘Can we make the CBAM work for India?’ Observer Research Foundation (ORF).

- Saptakee S (2024) ‘India Challenges EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)’Website: www.astrealegal.com

Posted by : Ms.Urvi Keche/ Ms,Mimansa Mishra

-

Email: contact@astrealegal.com Contact: +91 9822720483,

Disclaimer – This publication is provided for general information and does not constitute any legal opinion.This publication is protected by copyright. © 2025 Astrea Legal Associates LLP.